“My Lord! Increase me in knowledge.” (Qur’an 20: 114)

﷽

Muslms, Scholars, Soldiers.

Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions.

About Professor Adam R Gaiser:

This is his CV – curriculum vitae.

BA, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA. Major: Comparative Religion. MA, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. Major: History of Religions. Islamic Studies. PhD, University Of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. Major: History of Religions. Islamic Studies.

Current Position: Professor of Religion (or Associate Professor of Religion), Florida State University (FSU), Tallahassee, FL. Affiliated Faculty, Program in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, FSU.

His publications and books:

Book: The origin and development of the Ibadi Imamate ideal

Book: Shurāt Legends, Ibādī Identities: Martyrdom, Asceticism, and the Making of an Early Islamic Community.

Book: Sectarian in Islam: The Umma Divided. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023

First, one thing that you will notice when reading current works by Orientalist or Western Academics concerning the Ibadi school, is they are overly thankful to the Ibadi communities for the access to their libraries and manuscripts. This becomes a re-current theme.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many other scholars helped me during my year of research in Jordan; of special mention are ‘Abd al-‘Azīz al-Dūrī and Muhammed Khraysāt of the University of Jordan History Department, and Farūq ‘Umar Fawzī of the Omani Studies Department at Āl al-Bayt

University. My appreciation goes to Ahmad Obeidat, Islam Dayeh, and Nihad Khedair, my research assistants at the time (and now accomplished scholars of their own), for our many hours spent together in translation and discussion. I also thank the Omani Student Union in Amman, Āl al-Bayt University, and the University of Jordan, all of whom granted me unlimited use of their library and access to their manuscript collections. Further research took me to Muscat, Oman; thanks to Michael Bos, Shaykh ‘Abd al-Rahmān al-Sālimī, Shaykh Kahlān b. Nahbān al-Kharūsī, Shaykh Mahmūd b. Zāhir al-Hinā`ī, Dr. Khalfān al-Madūrī, Ahmad al-Siyābī, Shaykh Ziyād b. Tālib al-Ma‘āwalī of the Ma‘had al-‘Ulūm al Shar‘iyya, and to the students who shared their research and excitement. “

Source: (Acknowledgements: Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

“Fortunately, recent publications by the Omani Ministry of Heritage and Culture (Wizarat al-Turāth al-Qawmī wa al-Thaqāfa) of much of the Ibādī historical and legal corpus have made hundreds of works accessible to the researcher. In addition, the Libyan scholar ‘Amr Ennami collected and published several rare North African legal and theological works before his death.”

Source: (pg. 5 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

It is a common theme at least when engaging with Ibadism. That we are open and we give access to what people are looking for.

We had a brother mention an indiviudal who did an interview and claimed there was ‘gate keeping’ going on with us; this information came as a dissapointment. The individual knows better. We are doing our level best to get information about the Ibadi school out there. The western academics themselves acknowledge the tremendous help they have received in getting such access.

So first the unfortunate. Professor Gaiser continues to assert that the Ibadis were from the Kharijis, even though he knows better. He knows it is from heresiographical works. This is certainly dissapointing.

“As the sole remaining Khārijite subsect, the Ibādiyya are the last representatives of the opposition movement that was Khārijism, and the inheritors of its narrative and legal traditions.”

Source: (pg. 3 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

“One problem plaguing the study of the Ibādiyya and Khārijites is the uncritical reliance on either Sunni or Ibādī sources for historical narratives. Such an approach ignores the fact that these accounts were, to varying degrees, tailored to serve the polemical and

self-serving interests of the sect.”

Source: (pg. 5 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

Then why do Orientalist and western academics continue to use this terminology? The nomenclature of Ibadis being a sub sect of the Khawarij? So do take note to the orientalist and western academics reading this. Going forward why not point this out in the beginning of your works? That you are simply using Sunni polemical nomenclature that you find convenient.

“Caution should therefore be exercised when dealing with heresiographical texts, as the predilections of their authors, the structure of their texts, and reliability of their information are not always clear.”

Source: (pg. 15 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

Professor Gaiser makes a very interesting point here:

“Yet another flawed method of viewing the Khārijites is to interpret their activities through the lens of their most extreme or militant subsects. It is not uncommon to find, for example, a focus on the Azāriqa (or Najdāt), whose core activities lasted a mere fourteen years, as representatives of “the original Khārijite position.”This statement grossly overestimates the importance of the Azraqite subsect to the general history of Khārijism, and relegates the Ibādiyya, who have survived for thirteen centuries (and, incidentally, opposed the Azāriqa from the outset) to an undeserved historical footnote that does not reflect their longevity. Such distortions prevent an accurate appreciation of the role of Khārijite thought in shaping

the Ibādiyy…”

Source: (pg. 6 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

Professor Gaiser makes an interesting point here:

“In reality, it seems that the imām al-kitmān was a theoretical construct established in order to retroactively create Imāms out of the ‘ulamā’ who led the early quietist Khārijite movement in Basra (and who eventually established the Ibādiyya as a distinct Khārijite

subsect).”

Source: (pg. 13 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

However, he doesn’t seem to connect his ideas very well when later he states:

With the establishment of the Rustumid dynasty in Tahert and the first Ibādī dynasty in Oman, the practice of shirā’ was recognized to have potentially dangerous implications for the Ibādī state; the inherent danger of shirā’ lay in its latent ability to inspire rebellion in the name of Islamic justice. In an effort to diffuse the potentially destabilizing effect of shirā’, the Ibādī ‘ulamā’ developed the office of al-imām al-shārī as the leader of the shurāt. Likewise, the term shurāt, which had once referred to the early Khārijite heroes, became divorced from its original heroic connotations and came to specify the volunteer Ibādī soldiers who defended the Ibādī state against its enemies. In such a way, the practice of shirā’ was kept under the control of the Ibādī state. As a result, the practice of shirā’ changed from being a spontaneous practice to being a formal institution governed by social and legal regulations.”

Professor Gaiser makes a blank statement without really giving us much more. For exampe: Can practical examples be given in how the Ibadi ulama’ s development of the office of al imam al shari create stabliity? Especially considering his above statement:

“It seems that the imām al-kitmān was a theoretical construct established in order to retroactively create Imāms out of the ‘ulamā’”

What prevents the imam al-kitman from becoming the imam al-shari?

Ultimately there is nothing destablisizing about it. Rule with justice.

Do we consider any institute to be inheriently unstable because there are mechanism in place that prevent abuse of power?

One can attack a particuar lineage (alids) or tribe (quraysh) that could be a relatively easy feat. However, attacking and keeping an entire scholarly class under control is no easy feat.

Professor Gaiser often makes blank statements without telling us how he arrived at such conclusions.

“Likewise, distinctions between the imām al-zuhūr, imām al-shirā’, imām al-difā‘, and imām al-kitmān are not nearly as clear as post-medieval Ibādī imāmate theorists (and the non-Ibādī scholars who rely on them) would have us believe.”

What were the points of clarity that he felt were lacking? What did he think needed more elaboration? Especially given the knowledge that imām al-shirā’, imām al-difā‘ are more interm and temporary positons during a transition period.

So the reader has a few choices when it comes to this information.

1) Accept it blindly. Accept it as factual. Don’t think critically about the information.

2) Think about the information critically. Actually read the source and information that the school has written about it self and come to your own conclusion.

When we go through the foototes it is challenging to determine what sources Professor Gaiser relied upon for his information.

For those of you do not want to depend upon orientalist or western academis for information and would like direct access to Ibadi sources that speak on the subject we can provide the following:

“Masalik al-Dīn wa Atharuhā fī Ḥifẓ al-Wujūd al-Ibāḍī”

Author: ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz bin Suʿūd bin Sīf Ambusaidi

Supervisor: Ismāʿīl bin Ṣāliḥ bin Ḥamdān al-Aghbari

Examiner: Ibrāhīm bin Yūsuf bin Sīf al-Aghbari

Source: (https://maq.css.edu.om/home/item_detail/646)

Ghayat al-Murad fi Nazm al -I‘tiqad

Author: By the esteemed scholar, Shaykh Ahmed bin Hamed bin Suleiman al-Khalili (h)

The Grand Mufti of the Sultanate of Oman

We found another strange assertion of Professor Gasier here:

“The specific example of the Muhakkima’s attribution of sin to ‘Alī as the result of his agreement to arbitrate the Battle of Siffīn became the basis for the general Khārijite belief that sin makes a person an unbeliever (kāfir)—the Khārijite doctrine of sin. Although it is not explicitly stated in the sources, it is safe to assume that the attribution of sin/infidelity to an individual immediately disqualified that person from a position of authority over the Muslims, and thus, the connection between sin and ineligibility in leadership can be generalized to all Khārijite subsects.”

Source: (Pg. 39 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

Two major assumptions indeed.

- ‘Alī as the result of his agreement to arbitrate the Battle of Siffīn became the basis for the general Khārijite belief that sin makes a person an unbeliever (kāfir)—

- Although it is not explicitly stated in the sources, it is safe to assume that the attribution of sin/infidelity to an individual immediately disqualified that person from a position of authority over the Muslims

What is this based on?

Why would one think that Professor Gaiser be given a free pass to make such statements and yet, “we have to be careful what heriseiographers and even Ibadi sources say?

” Although this view is not explicitly stated in either early Ibādī literature or heresiographical materials, it is strongly implied by the doctrine of sin.”

Source: (Pg. 40 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

Even in the example Profesor Gasier has given:

“Certain evidence in heresiographical materials corroborates the application of the doctrine of sin to the Khārijite Imāms. It is reported, for example, that a faction of the Najdāt forced their leader, Najda b. ‘Āmir al-Hanafī, to recant and repent for his opinion that a person is excused from sin if he is ignorant of the fact that the action is a sin.”

Source: (Pg. 40 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

But did they remove him as the Imam or simply ask him to repent for his sin and retain him?

We are simlpy not told.

This information clashes with what Professor Gasier gives us here:

“A smaller section of the Najdāt then decided that it was not their place to question the ijtihād of their Imām, and forced Najda to repent his original repentance—which Najda did. As a result of this second repentance, the majority of the Najdāt deposed (khala‘ūhu) Najda and forced him to choose the next Imām.”

Source: (Pg. 40 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

If they forced him to repent of his original repentance and then deposed him it means that he was still their Imam when he initially repented. Thus the information Professor Gasier presents us clashes with his own conclusions!

Professor Gasier aslo states:

“However, an Imām who sinned or behaved in a way that was improper did not immediately become an illegitimate Imām. The Ibādī community gave him the opportunity to repent and make amends, such as the opportunity given to ‘Uthmān before his killing. If the Imām repented, he regained his proper place as leader of the Muslims. If he persisted in his sinful behavior, dissociation from him and active opposition to him then became a duty.”

Source: (Pg. 46 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

The above information makes it very clear that if an Imam commits a sin this in and of itself does not necessitate his removal from office. This again clashes with previous information presented by Professor Gaiser.

Alas, the informaton in the above paragraph presented by Professor Gaiser is incomplete and does not allow nuance. A very important point is the type and manner of sin the Imam commits. For example if the Imam committed adultery, and the proof is established against him there is no resuming the office of Imam. This should be clear from the perspective of jurisprudence.

Now let us turn our attention to something eslse Professor Gaiser says:

Alī as the result of his agreement to arbitrate the Battle of Siffīn became the basis for the general Khārijite belief that sin makes a person an unbeliever (kāfir)—

Source: (Pg. 39 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

He repeats this assertion here:

“Just as the Muhakkima’s rejection of ‘Alī on the basis of the sin of accommodating the arbitration of Siffīn formed the basis for later Khārijite doctrines of sin, so the acceptance of ‘Abdullāh b. Wahb al-Rāsibī further entrenched the precedent whereby piety became the main criterion for legitimate leadership.”

“Source: (Pg. 41 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

” Additionally, the qurrā’ at the Battle of Siffīn reportedly forced ‘Alī to accept arbitration against his better judgment, which is itself an indicator of a certain amount of authority.

Source: (Pg. 57 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

This raises all kinds of questions.

How could the qurrā on the one hand be the people who forced someone to accept something that they would see as the basis that makes a a person an unbeliever (kāfir).

“Similarly, the Muhakkima at Harūrā’ demanded of ‘Alī: “So repent as we have repented and we will pledge allegiance to you, but if not we will continue to oppose you.”

Source: (Pg. 37 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

Note 89 Foot note Source: Abū Mikhnaf in al-Tabarī, Tārīkh, 1:3353; see variants in al-Balādhurī, Ansāb al-Ashrāf, 3:123; Abū al-‘Abbās Muhammed b. Yazīd al-Mubarrad, al-Kāmil: Bāb al-Khawārij (Damascus: Dār al-Hikma, n.d.), 24.

” Additionally, the qurrā’ at the Battle of Siffīn reportedly forced ‘Alī to accept arbitration against his better judgment, which is itself an indicator of a certain amount of authority.

Note 46 Foot note Source: Abū Mikhnaf’s account in al-Tabarī, Tārīkh, 1:3330.

It is appreciated tht Professor Gasier gave the source for the sentiments above:

Abū Mikhnaf was a flamming hot chetto of a Shi’i. We are thankful that Professor Gasier mentions the following about him:

“The pro-‘Alid author Abū Mikhnaf portrays ‘Ammār as an early Companion of the Prophet Muhammed, and uses his story to highlight the illegitimacy of the Umayyad regime.”

Source: (Pg. 97 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

A Modern Historical Perspective: From a modern, academic historical viewpoint, Abū Mikhnaf’s value is immense. His bias is not dismissed but is itself a source of information. He represents the historical memory and narrative of the early Kufan Shi’a. Historians use his works to understand:

- How these early communities viewed themselves and their struggle.

- The political and social climate of 8th-century Iraq.

- The development of early Shi’ite identity.

The key is to use his material critically, comparing it with reports from other sources with different biases (e.g., pro-Umayyad historians). - Understanding the sectarian lens that are used when detailling events.

It is also not clear if Professor Gaiser sees the muhakkima and the qurrā as interchangeable names for the same group, or interchangeable groups. Or a singlular group that had divisons among themselves in regard to the arbitration.

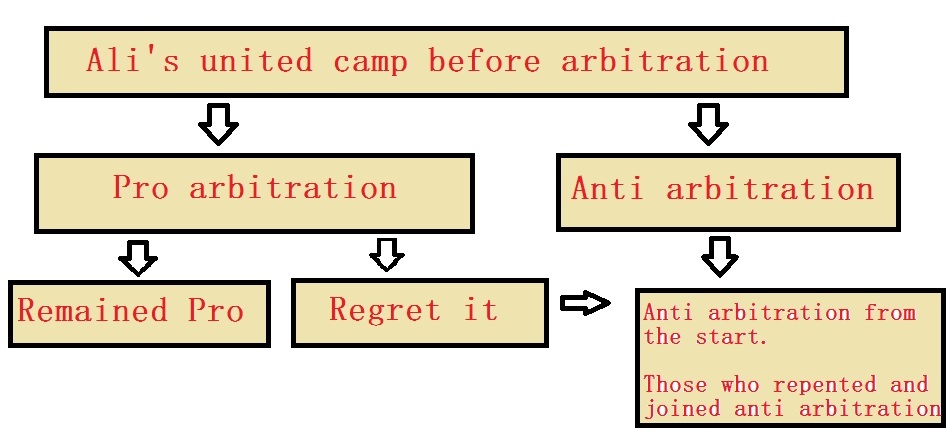

The following chart can help Professor Gaiser advance his claims. It can also make sense of what seems to be contradictory information. This is a possible model.

Unless Professor Gaiser contest that the Muslims had the Qur’an with them then on what consistent basis can he condidently say that rather than the event at Siffin that they simply did not draw from the Qur’an?

“And those who do not judge by what Allah has revealed are the ungrateful (l-kāfirūna).” (Qur’an 5:44)

No consideration is given to the idea that, as Qurra these people would be memorizers of the Qur’an and with the Qura’n not being a considerably large corpus, the warnings not to follow the people of the book the admonishment that those who judge by other than what Allah revealed are the disbelievers most likely echoed among them over and over.

This allows for Professor Gasier to present his thesis in a very clear way. That there were those who saw Ali’s decision as going against the clear guidance of the Qur’an. That he judged by other than what Allah had revealed. We know there were people who urged Ali to continue his fight against Mu’awiya.

There are those who were initially pro arbitration and a group from among them regretted that decision. That group joined up with those who were against it from the start. It is that group that says: “So repent as we have repented and we will pledge allegiance to you, but if not we will continue to oppose you.”

The only thing the Professor Gasier needs to do is follow the history and the logical conclusion. Committing a sin or an act of kuffar does not permanently preclude you from the office of Imam.

Additional thoughts. Not related to Professor Gaiser’s book, but one does have to wonder how Ali himself was viewed from the perspective of his followers. Rather, his followers and supporters were against his decision for arbitration or forced his hand. Either way, it seems like they had vastly different understandings of the authority of Ali than what the Shi’i masses are being told.

Professor Gasier states:

” Two points must be borne in mind when investigating how the medieval Ibādī institution of the imām al-shārī assimilated the early Khārijite phenomenon of shirā’, appropriated the Khārijite figures associated with the phenomenon of shirā’, and adapted the concept of shirā’ to a political institution of authority. “

Source: (Pg. 81 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

We were puzzled by this. Rather than appropriation from a stream that it is claimed they belonged to, why not just simply say they drew upon the Qur’an and examples of earlier martyrs?

You have to wonder how you appropriate from a tradition that you are already a part of?

“Unfortunately, North African jurists did not develop the notion of the shārī Imām, and therefore it remains a somewhat vague institution..”

Source: (Pg. 108 Adam R Gaiser: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions)

What is there to be detailed about it? The very title, Shira’ indicates that this office is a temporary office. Victory or Death. In victory you can be appointed as The Manifest Imam or you step down.

This particular office does not require a great deal of elaboration.

Over all the book is a very good read. It is not taxing. There is allot of information that one may find useful.

If you would like to read more about the four stages of the Muslim community you may read our article here:

May Allah Guide the Ummah.

May Allah Forgive the Ummah.